Human Rights in the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Industry’s role and responsibilities

Published: August 28, 2018

In July 2018, I spoke at the Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) international conference on Human Rights and Technology. The goal of the conference was to launch and inform the AHRC project to explore the impact of technology on our human rights. My role was to provide an international business perspective and to inform the attendees about the issue of bias in and impact of artificial intelligence on society.

I want to start a dialog about what we expect of the companies that create the technology that makes our lives easier but we have also become addicted to. I want everyone to think about our individual responsibilities as employees at these companies, consumers of the technology, and citizens of a government that may or may not regulate it. And I want us as a society to feel empowered to take action and ensure that technology works for ALL of us.

Why ethics in technology matters

My daughter is a daily reminder for me of why the issue of technology’s impact on human rights is so important. I see her zombied out on a mobile device and worry about addiction. I see stories of Artificial Intelligence perpetuating stereotypes or limiting options for women and I worry about AI making harmful recommendations against her. Each of us have people in our lives that we love dearly and who are at risk of technology limiting their rights and that’s why we’re here today. What kind of world do we want for ourselves, those we love, and future society?

“Coca-Cola, Amazon, Baidu and the government are all racing to hack you. Not your smartphone, not your computer, and not your bank account — they are in a race to hack you, and your organic operating system.” — Yuval Noah Harari, Wired Magazine

First Industrial Revolution

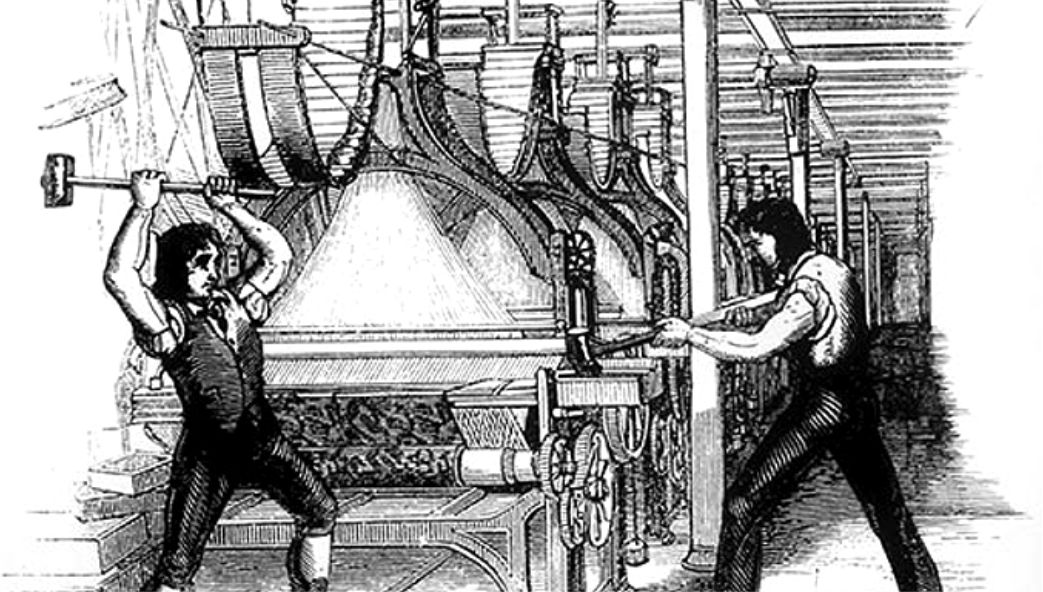

At the beginning of the 1800s, the textile industry in the United Kingdom employed the vast majority of workers in the North. It was a pretty good life! People could spin yarn or weave stockings from home. They rarely worked more than three days per week and were well paid, but the economy was hit hard after the Napoleonic wars and fashions changed so the merchant class that paid people for their work began looking for ways to shrink their costs. They not only began reducing wages, they started bringing in more technology to improve efficiency. These machines were larger and expensive so they built large factories to house them so people could no longer work from home.

Workers didn’t mind the technology — they used smaller versions of it themselves at home — but they objected to the harsh factory conditions, 14-hour days, and working six days per week. As merchants’ profits increased, they didn’t share them with the workers. Workers tried to negotiate better salaries and help for the unemployed to adjust to the new world but the merchants wouldn’t hear it. So these self-named “Luddites” banded together and began to destroy the machines that enabled the merchants to take advantage of the workers. They weren’t trying to hold back progress, they just wanted to be treated fairly by it.

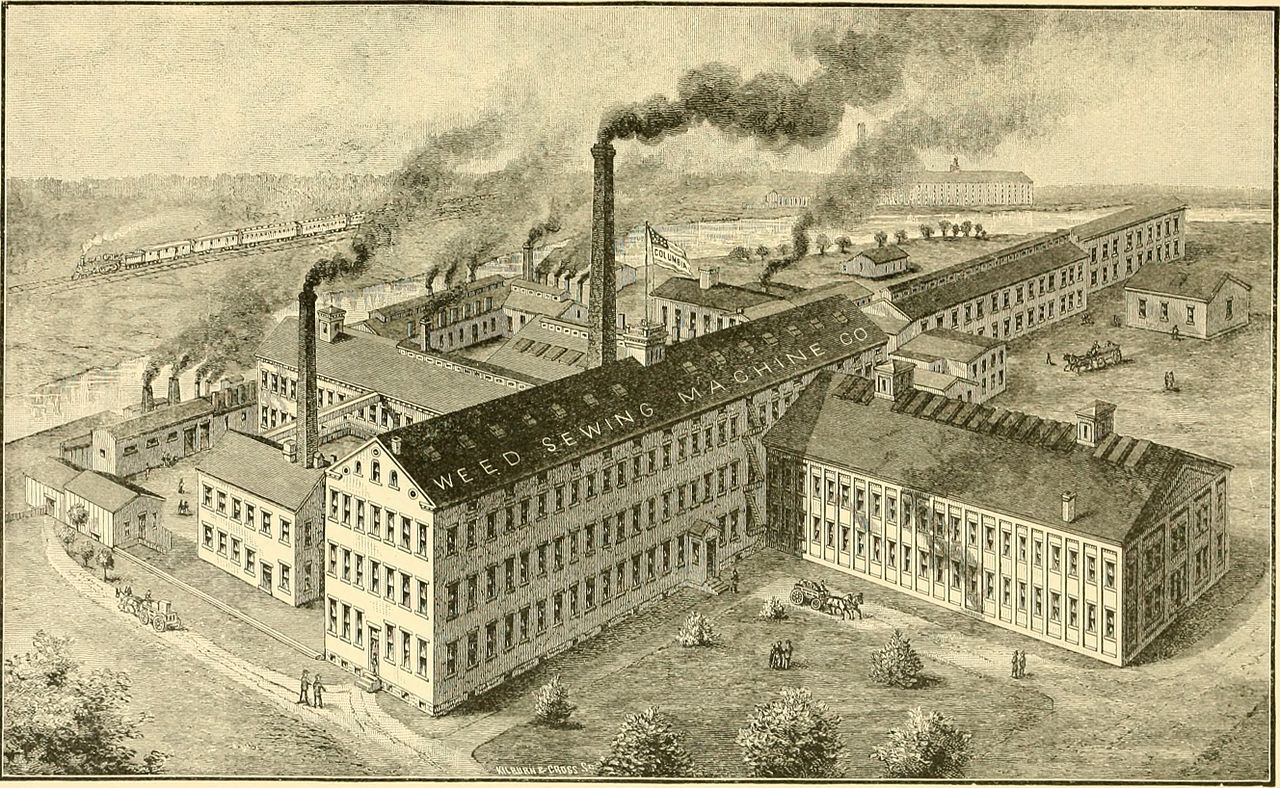

In the case of the Luddites, the story is usually focused on technology taking away jobs; however, more jobs were eventually created than lost. Unfortunately, those losing their jobs weren’t qualified for the new jobs being created.

The Luddite’s story is also about those in power using technology to provide an advantage to a few while disenfranchising many. Pollution from industrial activities, including coal power generation, impacted the health and lifestyles of workers and their families. For those that stayed employed, harsh factory conditions led to more injuries than from working at home. Although factory conditions have vastly improved in developed nations, it is not the case everywhere.

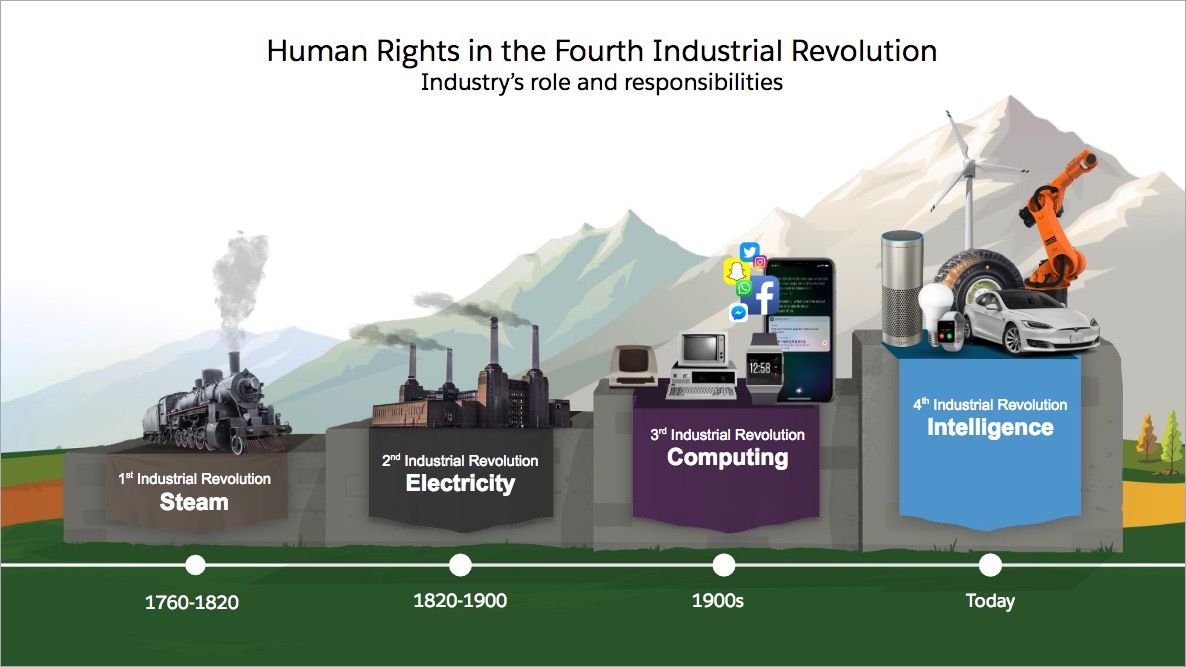

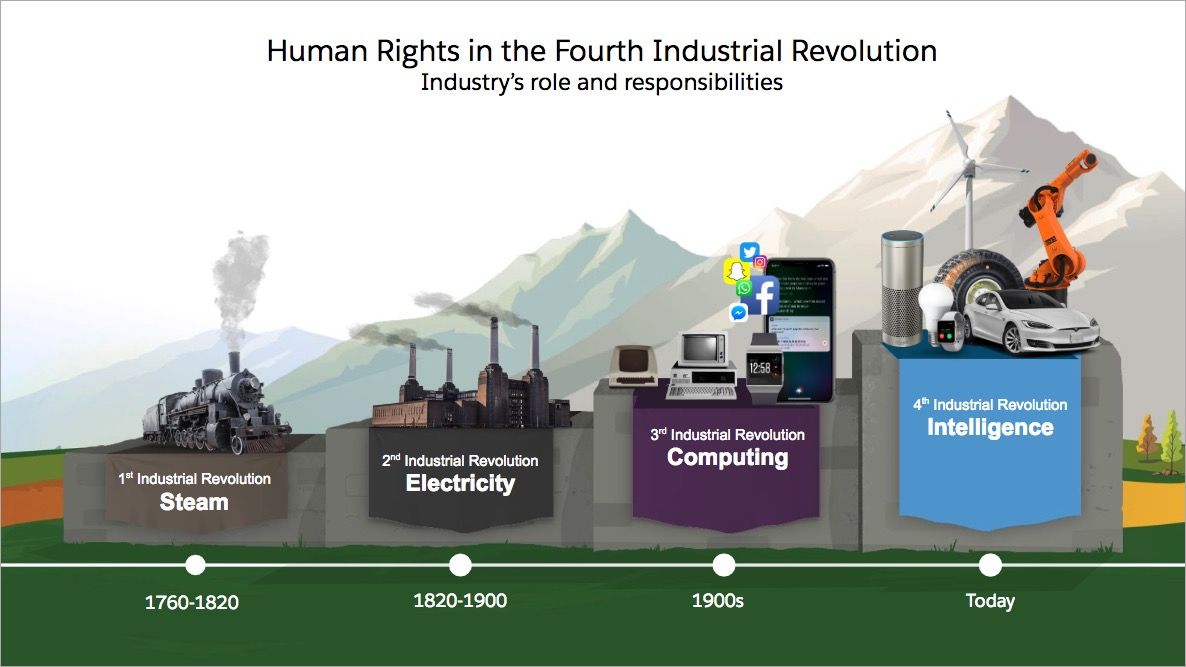

Fourth Industrial Revolution

That was the First Industrial Revolution. Today, we are entering the Fourth Industrial Revolution where artificial intelligence, robotics, and the Internet of Things (IoT) are transforming the world as we know it. What does that look like?

According to McKinsey Global Institute between 400M and 800M people around the world could see their jobs automated and will need to find new jobs by 2030. So far, those losing jobs or seeing their jobs scaled back are young, unskilled, and minorities. According to Pew Research Center, inequality in the US is at the highest levels it has been since 1928. New jobs will be created but those that have lost their jobs to automation will likely not qualify for them — at least not immediately.

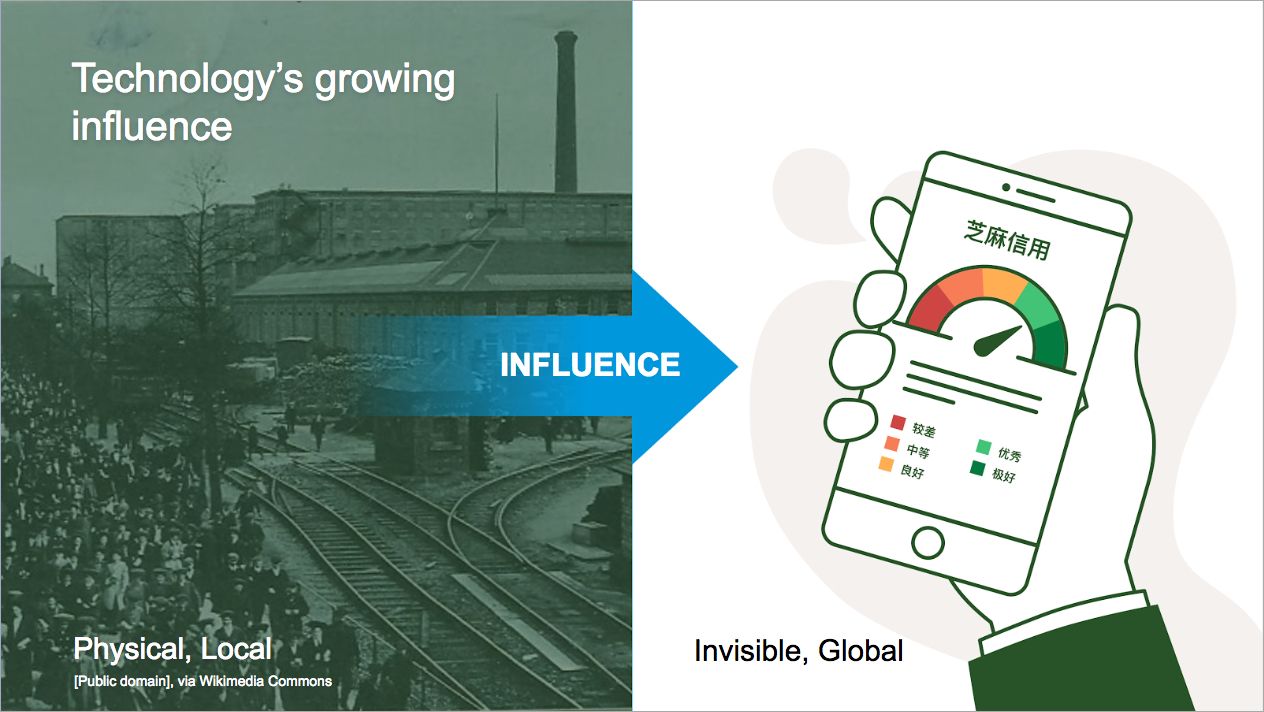

Over time, technology’s influence has changed from physical and local (e.g., factories, electric street lamps) to invisible, global, and omnipresent (e.g., Internet, facial recognition software, China’s social credit score). Amazon, Facebook, Google, Apple, and Baidu know us better than we know ourselves. Their algorithms are tracking everything we buy, where we go, what we read and watch, what we like, every step we take, and every heartbeat in our bodies.

Now, I’m no Luddite wishing to smash the machines of our oppressors. I’ve worked for big tech companies for the last two decades. I will be the first to talk about the many benefits of technology from longer life spans, to medical advancements like AI being able to detect tumors humans cannot and detecting Alzheimer’s before one’s family can to AI preserving indigenous languages. However, it is imperative that if we want AI to benefit society more than it harms, we must be aware of its risks and take action to ensure it is used responsibly. None are more responsible to ensure this than the businesses that create them. Government should be there to put checks and balances in place to ensure businesses do the right thing and punish those that do not but it starts with the creators!

Making Choices

Technology is about choices. As we embark on the 4th Industrial Revolution, we need to be clear about who is making the choices. Like Merchants in the 1800’s major tech companies today have the money and influence to implement technology at a greater scale than ever before but society is not impotent to accept the terms that are being provided. We have the power as citizens, consumers, employees, and governments to stand up and say we want to ensure technology works inline with human rights and not against them.

“The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to make people click ads. That sucks.” — Jeffrey Hammerbacher, Principal Investigator, HammerLab

Research shows that specific design choices can nudge behavior in positive directions like fitness apps or devices encouraging you to take more steps or meet your exercise goals for the week. They can also lead to addiction to social media or video games. We see this in our kids (and ourselves!) as we spend hours staring at our phones, jumping at the sound of incoming tweets, text messages, and other notifications that the system wants our attention.

If your phone buzzed in your pocket right now would you feel compelled to stop reading and glance at it to see what that notification means? Asurion’s 2018 Consumer Tech Dependency Survey found that 32% of Americans check their phone as soon as they wake up and 58% of respondents say they are addicted to their phones.

Designers have used knowledge of behavioral training and cognitive weakness in humans to create “sticky” experiences that keep us coming back for more. And because we can carry it with us in our pockets, we can get our fix any time, anywhere.

“AI is likely to be either the best or worst thing to happen to humanity.” — Stephen Hawking

Bias among us

There is no technology that dominates the headlines more today than Artificial Intelligence. It’s been widely acknowledged that it has both great potential and great risk.

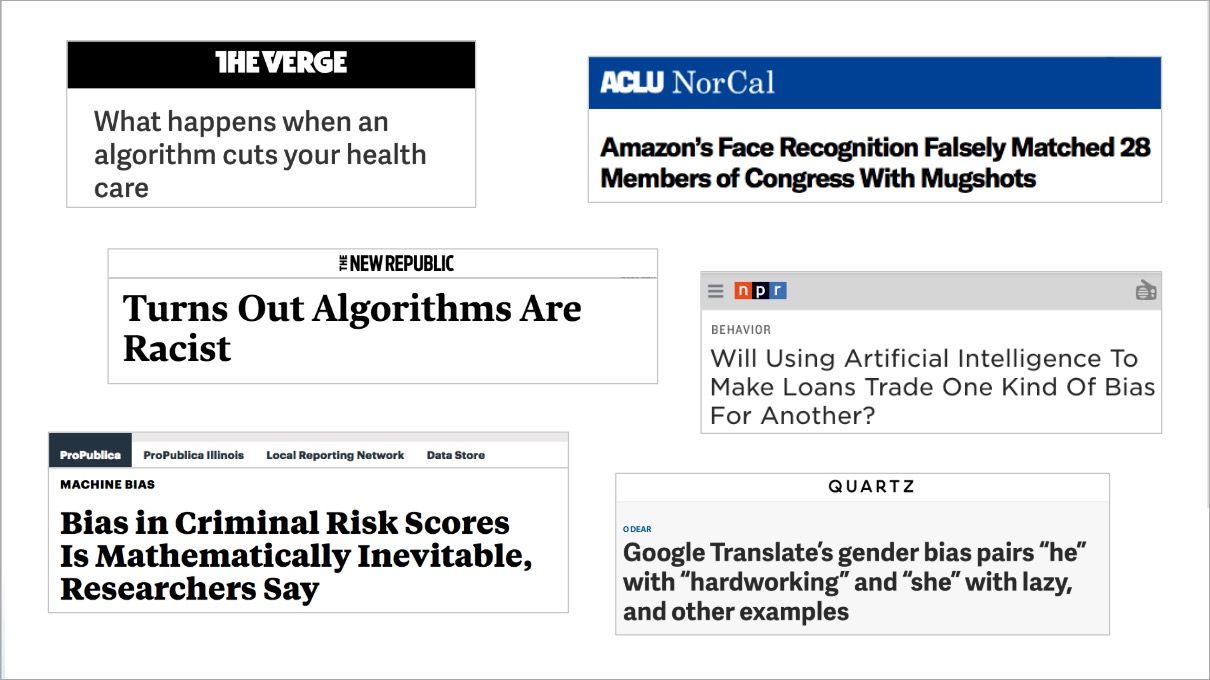

If you follow AI, you are likely inundated with stories of AI being racist, sexist, and perpetrating systemic bias. AI is not neutral. It is a mirror that reflects back to us the bias that already exists in our society. Until we remove bias from society, we must take active measures to remove it from the data that feeds and trains AI every day.

Why is the happening? Over and over again as I read the stories behind these headlines, I find that the intention of the creators was good. They wanted to create more fair and just systems. Unfortunately, bias in our data can be difficult to detect. Equally complicated is the definition of fairness.

What is fair?

Let’s use an example of a bank trying to decide whether an applicant should be approved for a home loan. An AI can make a risk assessment and recommend whether an applicant should be approved or rejected. AI can never be 100% accurate in its predictions of the future so there will always be some risk of error.

An AI may incorrectly predict that an applicant can repay a loan when actuality, he or she will not. It could also predict that an applicant will not repay a loan when in actuality, he or she will. As the AI administrator, you have to decide what your comfort level is for each type of error. The risk of harm here will either be greater for the bank or the applicant. Most companies may feel it is most fair to their shareholders to minimize the risk of financial loss but how much effort have they put into ensuring their data and algorithms are giving every applicant an equal opportunity of being considered on the merits of their ability to repay and not on systematic bias that runs through our society?

Race, religion, gender, age, sexual orientation…If you are using any of these in your decision, you may be disproportionately harming a segment of the population and violating their human rights. Even if you aren’t explicitly including these factors in your algorithm, there are often proxies in the data set for these factors. For example, in the US, zip code and income are a proxy for race because traditionally the US has had/continues to have populations of a particular race or ethnicity living in closer proximity.

“We need to have a more enlightened view about the role of companies. This company [Salesforce] is not somehow separate from everything else. Are we not all connected? Are we not all one? Isn’t that the point?” — Marc Benioff, Co-founder & CEO Salesforce

Corporate responsibility

Companies have a responsibility to think about these issues. They cannot simply claim a responsibility to their shareholders and optimize for minimal risk to the business. As Marc Benioff has said, companies are not separate from society. We are all connected.

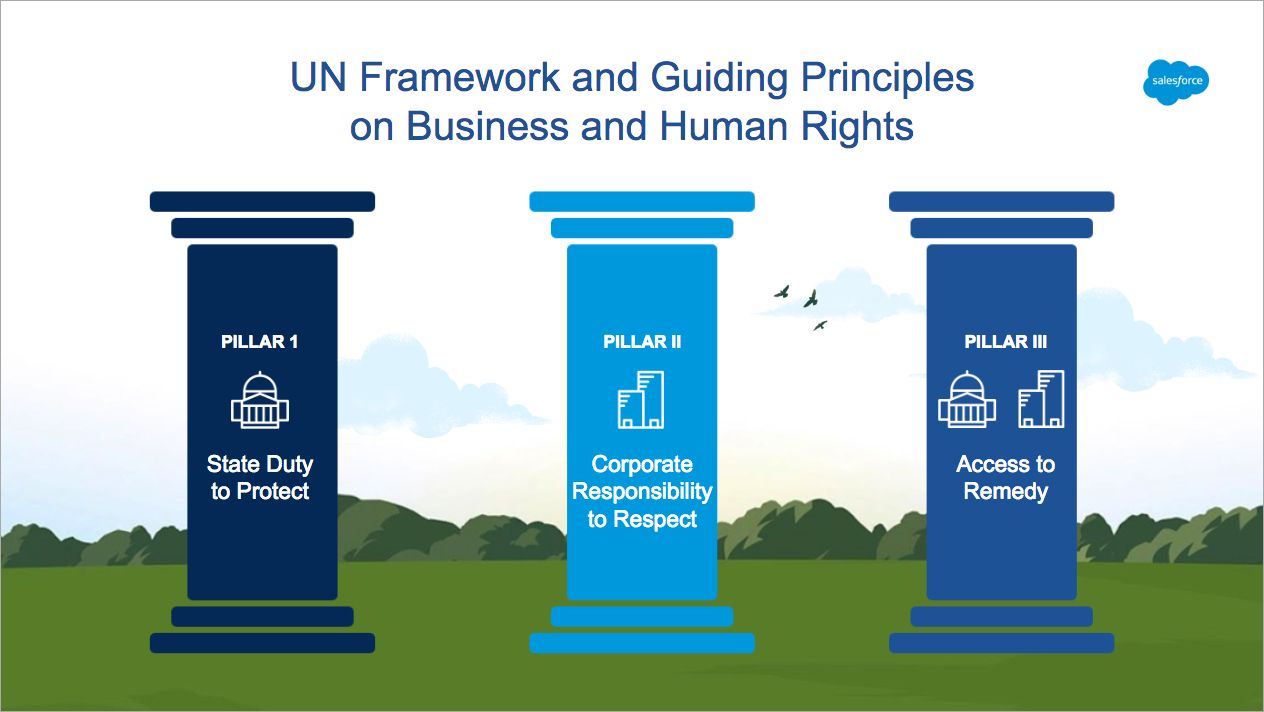

And we have a standard for how business should protect Human Rights. In 2011 the UN approved the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. It is the first global standard “for preventing and addressing the risk of adverse impacts on human rights linked to business activity.” As a society, we need to ensure that the companies we work for, buy from, and the governments that are here to protect us, are observing these pillars.

Due to public pressure, many companies are now starting to implement changes to deal with the negative behavior we are seeing from technology. Google and Apple recently announced new features like screen time, do not disturb, and notification controls to help people become aware of the phone use and take control over it, if they choose. IBM announced a new dataset to train facial recognition to see more skin colors. Accenture released a tool to combat bias in machine learning datasets.

I’m not here to suggest that companies should forfeit making a profit and focus solely on social justice. At Salesforce, we strongly believe that we can do well AND do good. You can make a profit without harming others and in fact, make a positive impact in the process. Companies do better in a society that flourishes!

Recommendations for Industry

So here are five recommendations for industry to do well and do good.

Salesforce’s values

Create an ethical culture: Understand your values and make every decision based on those values. Make sure employees understand what it means to work ethically. Here are Salesforce’s values. In addition, Salesforce is creating a course for PMs and engineers to on how to build ethics into our AI suite of tools called Einstein. Implementing ethics in AI is technically complex to design and build and so we need to ensure everyone knows how to do it. You also need to create incentive structures to ensure employees are rewarded when they live by those values.

Create a diverse culture: There was a great article in Scientific American in 2014 summarizing decades of research showing that diverse teams are more creative, diligent, and harder working. Lack of diversity results in biased products and feature gaps. We aren’t just talking about diversity of race, gender, and age. We also need diversity in backgrounds, experience, thought, and work styles. We need to create the space to challenge the status quo and each other.

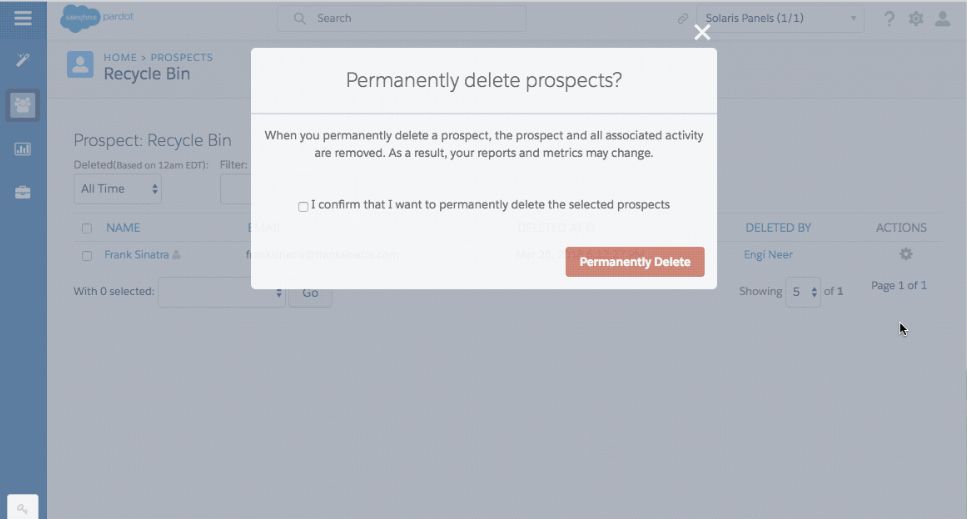

Empower users: Before designing any product or service, companies should obviously begin by deeply understanding their customers or users, their needs, and values. They should also empower them. The EU’s General Data Protection Regulations, requires companies to give users control over the data by allowing them to see their data, download it, and request to have it deleted. This is just good practice. Above you can see an example of Salesforce Pardot’s implementation of this here.

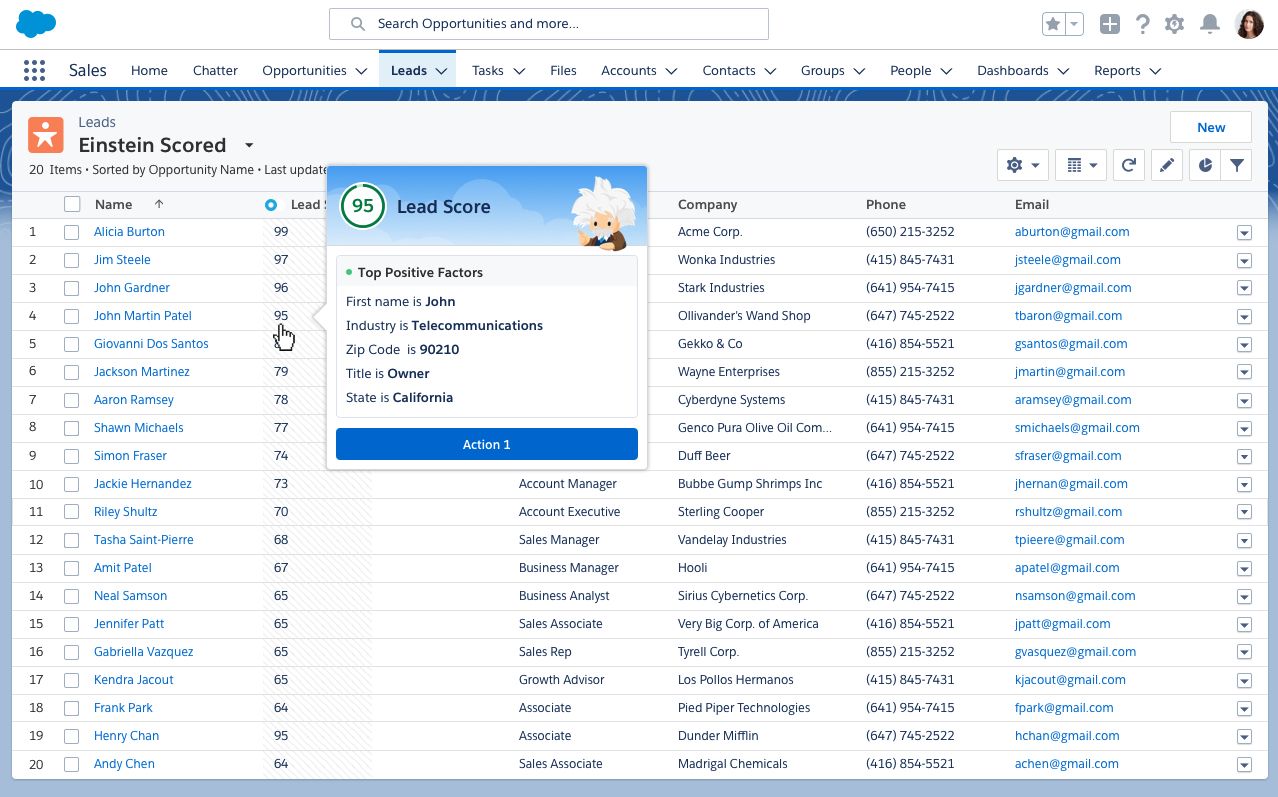

Remove exclusion: Companies must deeply understand their data and remove bias. They must also make algorithms scrutable to all. That is different from transparent. You could look at an AI’s algorithm and have no idea what it is doing so companies must communicate how it works in a way that is understandable. It must also monitor algorithms for bias and correct them. For example, in Salesforce Einstein Lead Scoring (above), we found that the strongest predictor of a sales lead is the name “John.” Now it seems silly that what you parents named you would make you a better or worse sales lead; but the AI doesn’t see it that way. It believes that if you have a traditionally female or non-Western name, you are a poor lead. That’s because the training data has a LOT leads with the name “John” in it. Since John is the most common male name in the US, this isn’t surprising but it also isn’t useful factor in prediction so we communicate that to users. Additionally, we are creating training modules in Trailhead, Salesforce’s educational platform, to teach our customers how to recognize bias in their data and remove it.

Partner with external organizations: There is no shortage of organizations to learn from and partner with including Access Now, Color of Change, Center for Humane Technology, World Economic Forum, AI Now, and Partnership on AI to name a few.

Businesses can be resistant to government regulation, arguing it can stifle innovation but it doesn’t have to be that way. At the Applied AI conference in San Francisco in April, presenters shared examples of collaborating with regulators like the US Food and Drug Administration on a new biotech device. Rather than slowing down their innovation, both the businesses and regulators learned more together than they could have apart and the AI creators to give assurances to their customers that their products were approved by the regulators. It is a win-win proposition!

“Technology must always challenge us. When we turn it off, we should be better than when we turned it on.” — Dr. Vivienne Ming, Managing Partner, Socos

It takes a village

In the end, we must realize that we are all in this together. We must be active in creating the society we want for ourselves and those we care about. Creators must be held responsible for their creations but we are all equally accountable for the products we choose to use (or not), companies we choose to work for (or not), and laws we choose to support (or not).

Thank you Jennifer Caleshu and Ian Schoen for all of your feedback!